FROM PALAU TO TEMPIO

by Thomas Forester

Rambles in the islands of Corsica and Sardinia

London 1858; 1861

Longman. Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts

in italian: ![]()

From Palau to Arzachena

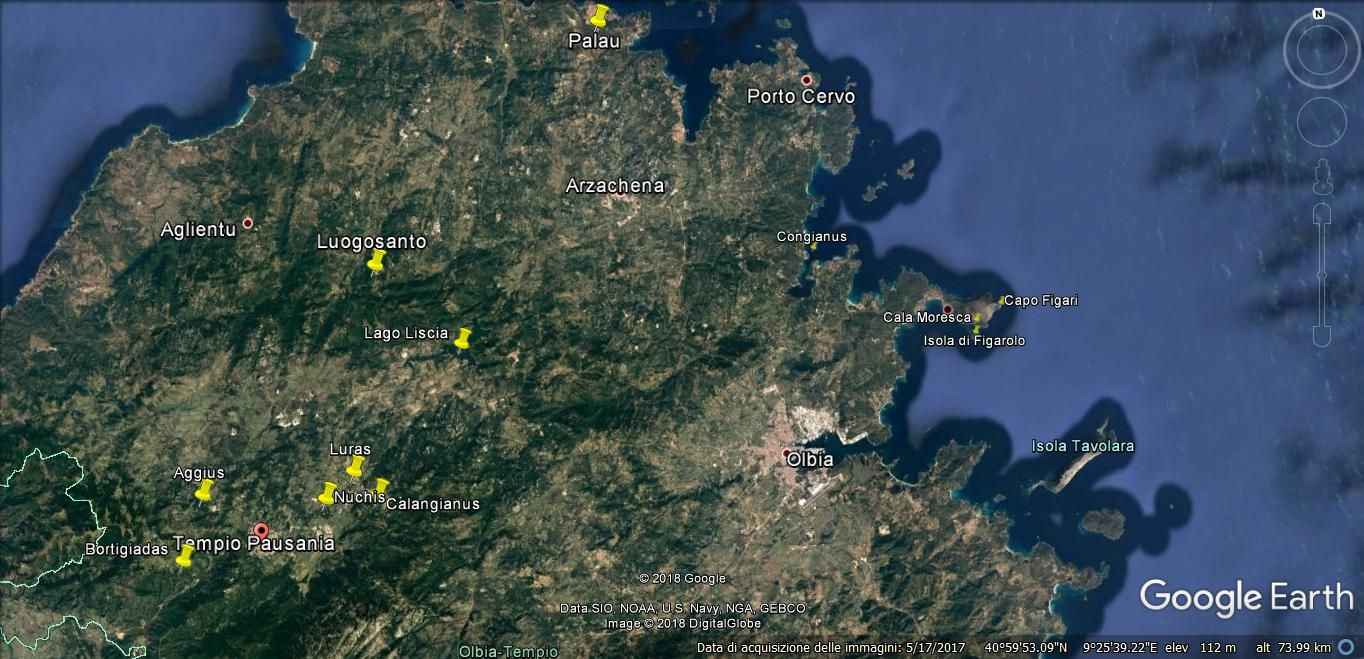

The halt at La Madelena was only a step in our route to the main island. We had still to cross a broad channel, and landing at Parao, on the Sardinian shore, horses were to be waiting for us. This arrangement, kindly made by Captain Roberts, required a day’s delay. We were to proceed to Tempio, in the heart of the Gallura Mountains, under guidance of the courier in charge of the post letters.

Ferried across the channel in less than an hour, we found the horses tethered among the bushes. House there was none, which must be inconvenient when the weather is too tempestuous for crossing the strait from Parao. We took shelter from the heat under a rock, making studies of a group of picturesque shepherds, and amusing ourselves with some luscious grapes, — baskets of which were waiting for the return of the passage-boat to La Madelena, — while a pack-horse was loaded with our baggage.

The outfit for this expedition was more than usually cumbersome, as it comprised blankets and other appendages for camping out, if occasion required. The cavallante, however, made nothing of stowing it away, cleverly thrusting bag and baggage into the capacious leather pouches which hung balanced on each side of the stout beast, with a portmanteau across the pack-saddle. When all was done, the cavallante mounted to the top of the load, where he perched himself like an Arab on a dromedary. […]

Nearly all the province of Gallura, washed by the Mediterranean on three sides, consists of mountainous tracts, with valleys intervening, similar to this of the Liscia. There is scarcely any cultivation, and they are uninhabited; almost all the towns and villages of the Capo di Sopra lying on the coast. On these plains a few shepherds lead a nomad life during the healthy season, being driven from them by the deadly intemperie prevailing in summer and autumn.

Until lately, the whole district was notorious for the crimes of robbery and vindictive murder, for the perpetration of which, and the security of the offenders, its solitudes and natural fastnesses afforded the greatest facilities.

Arzachena

Continuing our route we crossed some park-like glades, with scattered forest trees, and fringed by the graceful shrubbery, the macchia, common to both the islands of Corsica and Sardinia.

At some distance on our left (south-east) appeared a beautifully wooded hill, with a chapel on the summit, Santa Maria di Arsachena, one of the sanctuaries held in great veneration by the Gallurese. To these holy places they flock in great numbers on certain festivals, when the lonely spots, often hill-tops, surrounded by the most wild and romantic scenery, witness devotions and festivities, to which the revels form the chief allurement.

Luogosanto

There is a still holier place further to the south of our track, the Monte Santo, and I think its lofty summit, with a small chapel scarcely visible amid the dark verdure of the surrounding woods, was pointed out to us. It over-hangs the village of Logo Santo, well described as the “Mecca of the Gallurese.”

The sanctity of the place was established in the thirteenth century, the tradition being that the relics of St. Nicholas and St. Trano, anchorites and martyrs here A.D. 362, were discovered on the spot by two Franciscan monks, led to Sardinia by a vision of the Virgin Mary at Jerusalem.

A village grew up round the three churches then erected in honour of the Saints and the Blessed Virgin, with a Franciscan convent, long stripped of its endowments, and fallen to ruin.

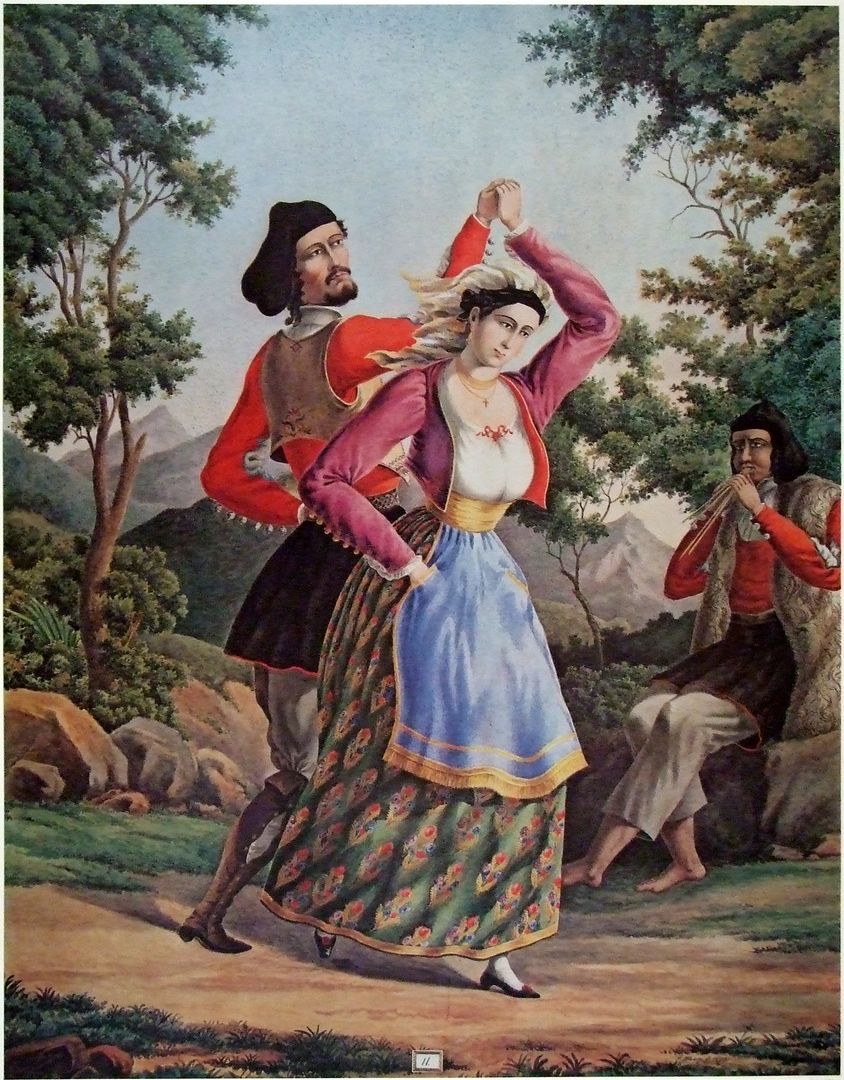

On the occurrence of the festivals celebrated at these holy places, the people of the neighbouring parishes assemble in multitudes, marching in procession, with their banners at their head; and the sacred flag of Tempio, surmounted by a silver cross, is brought by the canons of the cathedral and planted on the spot. The devotions are accompanied by feasting, dancing, music, and sports, the people prolonging the revels into the night, as many of them come from far, and the festivals occupy more than one day.

From Luogosanto to Tempio: a romantic glen, haunts of outlaws

After following the course of the Liscia for about an hour, we struck up a lateral valley, the water of which stood in pools, separated by pebbly shallows, but overhung by drooping willows, and fringed with a luxuriant growth of ferns and rank weeds.

The hills were covered with dense woods, intersected by rare clearings and inclosures on their slopes. Here and there stood a solitary stazzo, as the stations or homesteads of the few resident farmers are here called. We observed that they were generally fixed on rising ground. At some of these the courier stopped, his errands consisting not in the delivery of letters, that office appearing to be a sinecure in this wild track, but in leaving packets of coffee, sugar, &c., and, in one instance, a cotton dress, — commodities none of which had probably been taxed to the Customs at La Madelena.

Wayfarers in such countries generally select the right spot for their halt. This was a delightful one, and we fared well enough on the contents of a basket provided at La Madelena.

Again in the saddle, we soon afterwards entered a forest of magnificent cork trees, festooned with wild vines, relieving the sombre tints of the forest by the bright colours of their fading leaves. It hung on a mountain’s side, and the gloomy depth of shade became deeper and deeper, as, after a while, the dusk of evening came on, and we began to thread the gorges which led to the summit of the pass.

Salvator Rosa himself might have studied the wild scenery of Sardinia to advantage. If I recollect right, we are informed that he did. Nor would it require much effort of the imagination to add life to the picture in forms suited to its savage aspect, — to conjure up the grim bandit bursting from the thickets on his prey, or lurking behind the rock for the hour of vengeance on his enemy. Such scenes are by no means imaginary.

Some of the mountainous districts were in so disturbed a state that we were cautioned not to approach them; and every one we met throughout our journey was armed to the teeth. For ourselves, we felt no apprehensions, and took no precautions. In the first place, we were not to be easily frightened by possible dangers; and, in the second, we knew that a peaceable guise, in the character of foreign travellers, was our best protection. The violences of the fuorusciti are, it is well understood, mingled and tempered with a strong sense of honour. I imagine, indeed, that they originate for the most part in that principle, developed in vendetta, though degenerating into rapine and robbery. Outlaws must find means of subsistence as well as honest men, and are not likely to be very scrupulous as to the mode of obtaining them. Among such characters there will be miscreants capable of any crime, and therefore there is always danger. But, still, the virtue of hospitality to strangers, so inherent amongst the Sardes, as in most semi-barbarous races, is not extinguished in hearts which are hardened against every other feeling of humanity. […]

It appeared that, not very long since, my friend had kindly undertaken to conduct an English party from La Madelena to Tempio, the same route on which we are now engaged. The party consisted of an officer and his lady, and I believe some others. The lady was fond of sketching; attractive subjects, we know, are not wanting, and the indulgence of her taste caused frequent delays on the road, notwithstanding my friend’s repeated warnings of the ill repute in which that district was held in consequence of its proximity to the haunts of the banditti. Of all things the tourists would have rejoiced to have seen a real bandit, but, probably, under any other circumstances than in a wild pass of the Gallura mountains.

My friend, having politely suggested that he had not been remiss in pointing out the consequences of delay, replied that they must make for shelter in some stazzo, which they might possibly reach. Accordingly he led the way by a rough track through dusky thickets, and after pursuing it for some time, great was the joy of his companions at discovering a house, where they were received with great hospitality, and the promise of all the comforts a mountain farm could offer.

Then the banditti rushed in with fierce gestures; truculent men, with shaggy hair and beards, wrapped in dark capotes, with long guns in their hands, and daggers in their belts and bosoms. “Spare our lives, and take our money, and all that we have,” was the cry of some of the travellers. Nor were the bandits slow in falling upon the sacs and malles, and beginning to rummage their contents, without, however, offering the slightest molestation to any of the party, who stood aghast witnessing their movements.

The travellers found that they were safe, and, recovering from their panic, finished their supper with renewed gaiety.

The outlaws withdrew, but shortly returning, some of them accompanied by their wives and children en habits de fête, the evening was spent in the exhibition of national dances, with songs and merriment. This formed the concluding scene in the little drama which my informant had got up for the gratification of his friends.

No such thoughts as those suggested by the occurrences just related occupied our minds while we ascended the defile which penetrates the mountain chain intervening between Tempio and the valleys terminating on the coast.

The savage character and the traditions of the locality might have inspired them, but we were under the protection of the courier, a privileged person — probably for good reasons, — and, besides this, as I have already said, under no sort of personal apprehension.

Our attention was divided between the stern magnificence of the gorge, the more striking from its being now half veiled in darkness, and the difficulties of the ascent which, as usual, increased step by step, until, at last, winding stairs cut in the rock surmounted the highest cliff’s and landed us at the summit of the pass.

Late as it was, the ride would have been highly enjoyable, in that pure atmosphere, with the vault of heaven blazing overhead, and the stillness of the night broken only by our horses’ hoofs, but for the weariness of the poor beasts after a long day’s journey and the toilsome ascent of a mountain pass, and the ruggedness of the tracks along which we had to pick our way. Welcome, therefore, were the lights of Agius, Luras, and Nuches, villages standing some little way out of the road, at from two to three miles’ distance from Tempio. These places, Agius in particular, were formerly notorious for robbery and vendetta, notwithstanding which the population, which is chiefly pastoral, has always maintained a high character for kindness, hospitality, industry, and temperance.

Our path lay now through very narrow lanes, dividing vineyards and gardens, extending all the way to Tempio.

ILLUSTRATION SOURCES

19th Century Paintings, Drawings and Lithographs (captions translated freely)

Michel Antony Shrapnel Biddulph, Valley of the Liscia, ca 1858 [figure and original captions are in this book of Forester]

Philippine de La Marmora, “The ancient church of Our Lady near Tempio [Luogosanto]”, 1854-1856, IN Luigi Piloni, Memorie sulla terra sarda: tempere inedite di Philippine de la Marmora (1854-1856), Cagliari, Fossataro, 1964.

Simone Manca di Mores, “The Sardinian dance in the square of the church”, ca 1861-1876, IN Simone Manca di Mores, Raccolta di costumi sardi, Cagliari, Della Torre, 1991.

Salvator Rosa, figure in this book.

Alessio Pittaluga, “The Gallura shepherd”, ca 1826, IN Royaume de Sardaigne dessiné sur les lieux. Costumes par A. Pittaluga [lithography engraved by Philead Salvator Levilly], Paris – P. Marino, Firenze – Antonio Campani, 1826, rist. Carlo Delfino 2012.

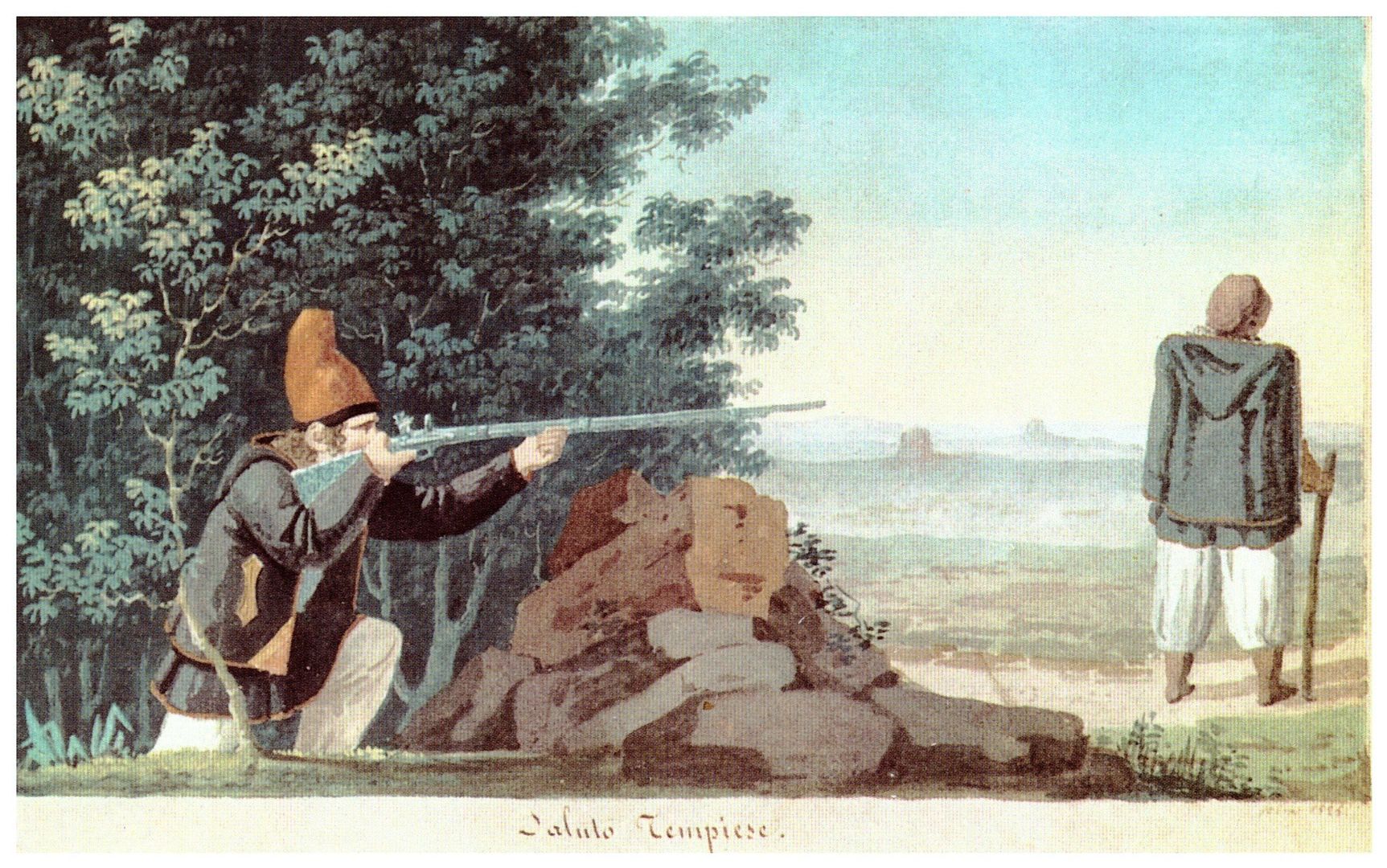

Giuseppe Cominotti, “Greeting from Tempio”, 1825, IN Francesco Alziator, La raccolta Cominotti: raccolta di costumi sardi della Biblioteca Universitaria di Cagliari, ed. De Luca 1963 e Zonza 1990.

Giuseppe Cominotti, “Country conversation”, 1826, IN Francesco Alziator, La raccolta Cominotti op. cit.

William Light – Jean [Giovanni] Micali, 1829-1830 (1 – 2 – 3)

Lorenzo Pedrone, “The Gallura shepherd”, ca 1841, IN Luciano Baldassarre, Cenni sulla Sardegna, illustrati da 60 litografie in colore, Torino, Botta, 1841; Torino, Schiepatti, 1843 (rist. Archivio fotografico sardo, 1986, 2003).

Manca di Mores, “Dance to the sound of the launeddas”, ca 1861-1876, IN op. cit.

Postcards and Photos, Late 19th/Early 20th Century

coll. Francesco Cossu

Contemporary Photos

map by google earth

Matteo Merlin – Flickr; Antonio Concas – Flickr; Martin Croonenbroeck – Flickr; Aurelio Candido – Flickr; Immacolata Ziccanu – Flickr; Vittorio Ruggero – Flickr; Hans Leysieffer – Flickr.

![Michel Antony Shrapnel Biddulph - Valle del Liscia [picture in the book], 1858 Michel Antony Shrapnel Biddulph - Valle del Liscia [picture in the book], 1858](https://www.galluratour.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2A-Biddulph-la-valle-del-Liscia-1858.jpg)